Capturing Objects Weakly In Instance Method References In Swift

One of my favorite features of Swift is the fact that functions are first class values: they can be assigned to variables, passed around as arguments to other functions, and manipulated and decorated in numerous ways. You can even do this with methods on classes, structs and enums, since every type of function is represented in the same way in Swift.

When writing swift code that interfaces with classes like NSNotificationCenter that have block-based APIs, you can take advantage of this fact by defining a method to respond to notifications, and just pass that method reference along to the notification center.

Consider the following class definition:

class MemoryCache {

var observer: AnyObject?

init() {

observer = NSNotificationCenter.defaultCenter().addObserverForName(

UIApplicationDidRecieveMemoryWarningNotification,

object: nil,

queue: NSOperationQueue.mainQueue(),

usingBlock: self.clearMemory)

}

deinit {

NSNotificationCenter.defaultCenter().removeObserver(observer)

}

func clearMemory(notification: NSNotification!) {

// ... do some nontrivial work to empty the cache here

}

// ...

}Here when we initialize the cache, we listen for memory warning notifications and respond using the given clearMemory method. We reference self.clearMemory without the parens at the end which just takes the clearMemory method as a function value and gives it to the addObserverForName function.

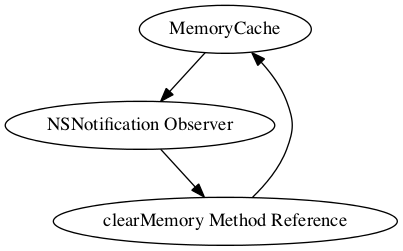

Though this looks nice, there’s one very large caveat: when you reference an instance method in this way and store the method value elsewhere, that method strongly references self. If it didn’t, your program could crash if the method value outlived the instance that it was bound to. Not crashing is important, but in this scenario it causes a retain cycle, since MemoryCache strongly references the notification observer, which strongly references the given closure, which strongly references the MemoryCache:

At this point we could just cave in and pass a closure into the usingBlock: parameter that weakly captures self, but that seems a little superfluous here if we only are going to call one other method in that closure anyways (and it’s not as fun!)

One valid way you could get around this in some cases by using the target-action pattern from objective-c, but that only works for classes annotated with @objc or that inherit from NSObject (which our MemoryCache does not), and with classes that provide target-action based methods. If we want a more idiomatic Swift solution that is more broadly applicable, we need to think of a better way.

A viable solution needs a way to make the instance method we want to call reference self weakly, and do the right thing when the weak self reference happens to be nil. To do this, we need to take advantage of another neat swift feature: static method references.

Static instance method references are an esoteric feature of Swift types. To get a raw reference to the clearMemory method in swift, you can do this:

let clearMethod = MemoryCache.clearMemoryNote that we’re referencing the clearMemory method as if it were a static/class method and not an instance method. This is valid, but the type of this method may be unexpected:

(MemoryCache) -> (NSNotification!) -> ()This type is bascially a function that returns a function (also known as curried or partially-applied functions). The function takes a parameter of type MemoryCache, and returns another function with the type (NSNotification!) -> (), which is the type of the actual clearMemory method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

// create the cache

let mycache = MemoryCache()

// apply the clearMemory static method reference to the cache object

let clear = MemoryCache.clearMemory(mycache)

// actually perform the clearMemory method on "mycache"

clear(notification)

Line 4 above applies the mycache value to the function that gets returned and stored in the clear variable. Here, any references to self in the originally defined clearMemory method are bound to the value of mycache, and this is where the retain cycle issue manifests: MemoryCache.clearMemory(mycache) is equivalent to mycache.clearMemory. Line 6 above performs the clearMemory method, as if we had simply called mycache.clearMemory(notification).

With all this in mind, we now have a way to create a function using the static method reference of the clearMemory method that will be able to weakly capture a reference to self. This function needs to return a function of type (NSNotification!) -> () that we can give to the addObserverForName method, and the function we’re returning needs to call the staticaly referenced method only if the parameter representing self is not nil. This function looks something like this:

func weakify(owner: MemoryCache, f: MemoryCache -> NSNotification! -> ()) -> NSNotification! -> () {

return { [weak owner] notification in

if let owner = owner {

f(owner)(notification)

}

}

}The function we’re returning effectively does the same thing as the closure we gave to NSNotificationCenter in the original example. Now if we apply this new function to our example, we get this:

class MemoryCache {

var observer: AnyObject?

init() {

observer = NSNotificationCenter.defaultCenter().addObserverForName(

UIApplicationDidRecieveMemoryWarningNotification,

object: nil,

queue: NSOperationQueue.mainQueue(),

usingBlock: weakify(self, MemoryCache.clearMemory))

}

deinit {

NSNotificationCenter.defaultCenter().removeObserver(observer)

}

func clearMemory(notification: NSNotification!) {

// ... do some nontrivial work to empty the cache here

}

// ...

}Weakly capturing self without having to worry about our own closure. Nice!

However, this weakify function is not very reusable; what if we wanted to use this in a completion handler for a UIViewController presentation, or as a callback for a response to a network request? As this function currently stands, we can’t due to the types it expects. However, we can take advantage of generics here since the exact parameter types don’t matter in the context of weakify: we’re just decorating a function and passing its parameters along. The weakify function below works with all methods that take one parameter and return nothing:

func weakify <T: AnyObject, U>(owner: T, f: T->U->()) -> U -> () {

return { [weak owner] obj in

if let owner = owner {

f(owner)(obj)

}

}

}T will represent the type of the class instance you need to be made weak. It must be constrained to AnyObject, since the you cannot make weak references to struct/enums. When used to weakify the clearMemory method, T will represent the MemoryCache and U will represent NSNotification!.

There are other weakify functions one could write too. One useful simple example is a method that takes nothing and returns nothing. Say our MemoryCache class also had a way to persist the cache to disk when we got a memory warning:

extension MemoryCache {

func persistToDisk() {

// ...

}

}Disk access should not happen on the main thread, so you could use grand central dispatch to make that happen on a background queue:

dispatch_async(dispatch_get_global_queue(DISPATCH_QUEUE_PRIORITY_DEFAULT, 0),

weakify(self, MemoryCache.persistToDisk))If it’s desirable for the memory cache to deallocate before this operation gets the chance to run on the background queue, this will make sure it happens safely. The weakify function we need to implement for this use case is simple:

func weakify <T: AnyObject>(owner: T, f: T->()->()) -> () -> () {

return { [weak owner] obj in

if let owner = owner {

f(owner)()

}

}

}Given the static method reference that returns a function of the type () -> (), this returns another of the type () -> () that executes the original method as is if owner is still valid.

Another example is a weakify that takes no parameters but returns somehing. The type signature of that would look like this:

func weakify <T: AnyObject, U>(owner: T, f: T->()->U) -> () -> U?Here we have an input function that takes a T and returns a function that takes nothing and returns a U. The return value of this weakify function may seem odd at first: why does the resulting function have to return an optional U when the given method returns a non-optional U? The body of the function should answer that:

func weakify <T: AnyObject, U>(owner: T, f: T->()->U) -> () -> U? {

return { [weak owner] in

if let owner = owner {

return f(owner)()

} else {

return nil

}

}

}Weak references must always be optional, so that the type system can represent what happens when said reference is removed from memory. If owner here is nil, it would not be possible to call the given method reference since it expects a non-optional value. Since we must return something according to the method signature, the only thing we can reasonably return here is nil which necessitates the U? return type of the resulting function.

There are some crazy applications you can do here if your use case needs it. You could cast values within weakify, for example, if you were using an API that requires a potentially unsafe downcast from the type that the method you want to use expects as a parameter:

func weakify <T: AnyObject, U, V>(owner: T, f: T->U?->()) -> V -> () {

return { [weak owner] obj in

if let owner = owner {

f(owner)(obj as? U)

}

}

}In this one, V represents the type of the closure or block that is expected by the API consuming your weakified method. The method we are weakifying must accept an optional argument, because we’re casting to U from V with the as? operator since it is not guaranteed that the type represented by V can be safely cast to U. You could write a version of this that took a method of type U->(), but you would need to use the as! operator (or the as operator in swift 1.1 and earlier) instead, which runs the risk of crashing your program if the argument types aren’t convertible safely.

If you find yourself wanting to use these weakify functions, check out this gist which has all the weakify functions defined here and them some. If you have any questions, comments, or suggestions, reach out to me via email (kevin@klundberg.com) or Twitter. Enjoy!